Building a Record Label from a Street Merch Empire

Running Press

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links, meaning The Fan Files will receive a small commission if you choose to purchase through any of the below links.

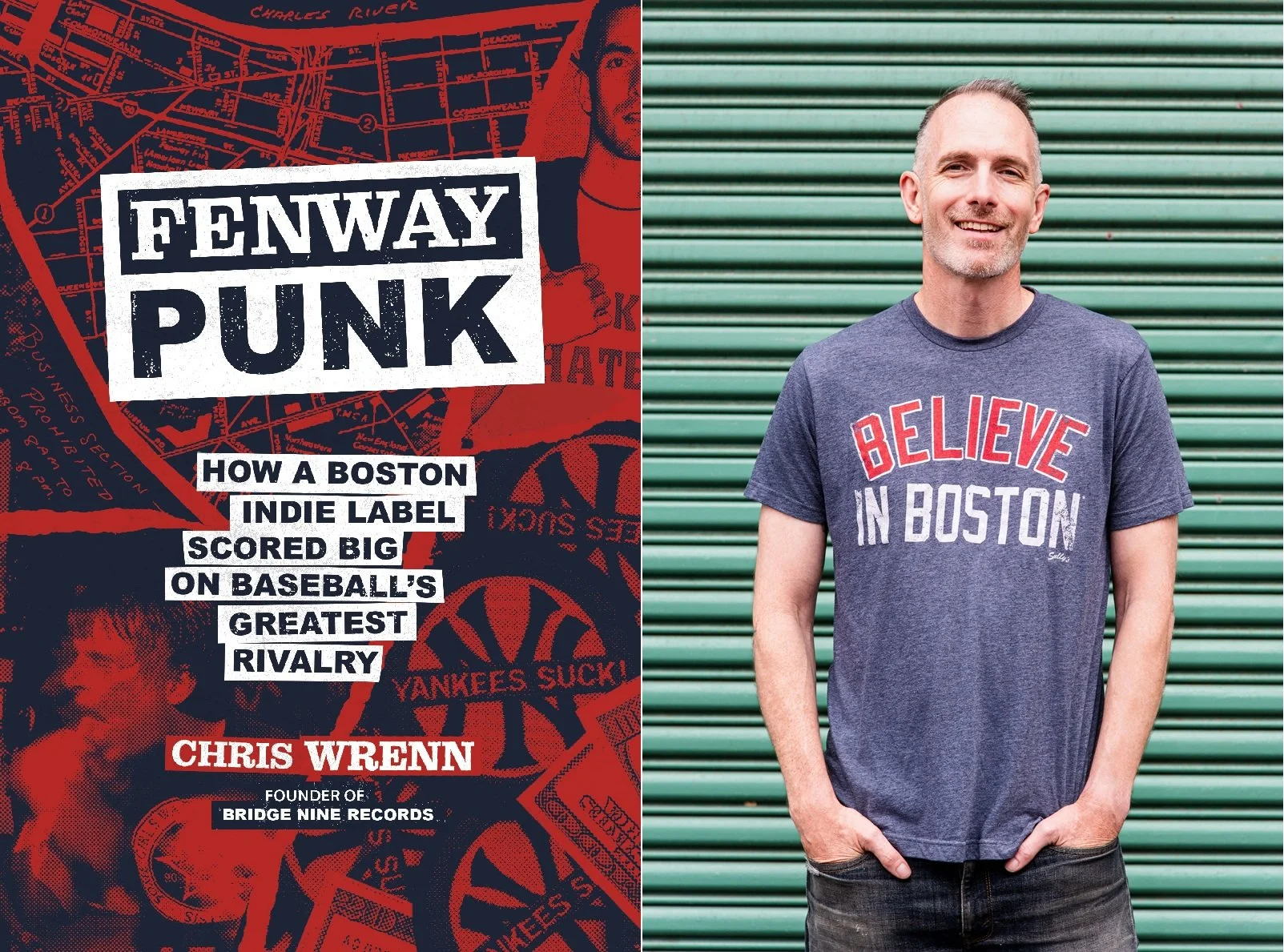

Chris Wrenn spent his youth with an entrepreneurial, DIY, punk mindset. Short on cash and wanting to start a record label in the Boston hardcore punk scene, Wrenn started selling “Yankees Suck” stickers on the blocks outside of Fenway after games. Those sticker sales led to tshirt sales, which led to the funds he needed to begin his label as well as a thriving sports merchandising company.

In his book Fenway Punk: How a Boston Indie Label Scored Big on Baseball’s Greatest Rivalry, Wrenn paints a story of his youth and how his love for music and his entrepreneurial spirit intersected with the storied rivalry between the Yankees and the Red Sox. In the following conversation, Wrenn speaks to the book’s origin, fan interactions, and other best selling slogans.

What led you to write Fenway Punk?

It was my salad days. I lived a mile away in the downtown Boston area amongst all my friends. People would always tell me, “This deserves to be documented.” I just finally just sat down and started writing.

Reading the book now, it feels like a very cohesive narrative. Before you started working on the book, did you have that direct connection of, “selling these shirts helped me start the record label”? Was that always the story of the business?

Yes. That was always the foundation. When you're 19, 20, 21, you want to do something like start a label, you don't know what resources are available to you. There might have been other opportunities that I wasn't familiar with or wasn't on my radar. For me, I had a track record of just, “all right, I need this, so how do I get to that?” If I need $1,000, I'll figure out how to make that, and then I'll put it into whatever it is I want to do. From the beginning, I saw the opportunity at Fenway as a way to earn money to release albums on Bridge Nine.

I am curious, because money has changed so much with inflation and rising costs. At the time, you're talking about $1,000 and directly translating that into recording time. Would the math still work today? If you were making the same vague amount of money selling shirts, would you be able to record a track now?

You definitely could. In fact, if anything, the cost of recording has gone down because there are just more streamlined means to do it. I think the way we earned the money, being a street-based, in-person cash business, that really wouldn't exist. I think at the time, 2000 to 2004, that window, this is really before a lot of e-commerce. Obviously, e-commerce existed, but it wasn't the go-to. This was before the Amazon, I think even before the Googles. At the time, there was that impulse, I need to buy something right now, because otherwise I'm not going to have that opportunity. I think, now, when people are leaving a game at Fenway, there's no have to do it at that moment. The opportunity to sell things, I think, has shifted.

What was your weirdest run-in with a Boston fan?

Weirdest run-in with a Boston fan? I don't know. We would have people that were so excited to see us and people that were so angry with us. It wasn't mutually exclusive to a team or to a fan base. We would have Red Sox fans that were just so angry with us because the Red Sox were down 15 games in the standings, behind the Yankees. We would have Yankees fans that thought what we were doing was so funny and they loved it, that they would buy stuff as almost just to commemorate their trip to Fenway, like, “I got this thing that makes fun of the Yankees.” We would just engage with people on multiple levels of sobriety after games from both sides of the fence.

The Yankees Suck slogan did really well. What other slogans did well? You mentioned there was the gun one as well, but what stood out?

That one was the Curt Schilling, Killing with Schilling t-shirt. Again, he was number 38. At the time, it was riffing on the caliber of a 38 pistol. People referred to pitchers as guns, so it was an easy shirt to make. I mentioned in the book, I think we sold 2,000 of them before he even pitched his first game for the Red Sox.

That's crazy.

People were excited about moves that the Red Sox were making at that time. We were selling year-round at that point. We would be at the Garden selling T-shirts to people leaving hockey and basketball games. Obviously, there's so much crossover with all the teams and their fan bases.

Obviously, you had to keep somehow in the know with the major news, but you also weren't going to games because you were working. How did you manage that?

A lot of listening to games, reading the newspaper headlines and reports afterwards, just being aware. Everyone knows what's going on during a homestand, for the most part, just amongst friends and other fans.

Was there a slogan that you wish you tried and you never got around to making?

We've had a series of Fight Club t-shirts that we've made over the years. Our most popular one, I think, was the Joe Kelly Fight Club that we made in 2018. I wish we made a Varitek Fight Club shirt in 2004. We made it to acknowledge and commemorate the 20th anniversary of his 2004 issue with A-Rod. That's been very popular. I wish we had started that franchise back in 2004.

We had one t-shirt that I don't think I mentioned in the book, but it was “Jeter Drinks Wine Coolers” that one of my employees pitched in 2004. It would have been right during that 2004 season. I was like, “No, I don't know. I think that's dumb.” I sidelined it. Then in 2005, I was going through the idea box, just trying to come up with things for the new season. I said, “You know what, let's give that a try.” That was one of our best-selling t-shirts in 2005.

One of the things that stood out to me about your book is you had this mindset of expanding. It wasn't just got to make the money to just do the label. It was also, how do we print our own shirts? How do we streamline our business? Were you thinking of these businesses as parallel growth or were you still thinking of the merch as a means to an end?

I think it was all means to an end. We started printing our own t-shirts because of the cost savings and the convenience and the becoming more of a priority. I had a good relationship with my screen printer before that, but they got a little tired of me going in there every day being like, “Oh, my God, I need this right now.” Being able to take that in-house was a huge help.

I think at the time, I wasn't thinking of starting an additional business, but that's how these things happened. I would start doing something, whether it was what became Sully's Brand in an effort to fund Bridge Nine and then realizing, “Oh, we should be making our own T-shirts. At first, we'd do it as Sully's, but then, you know what, let's start another screen printing business. That way, we don't just make things for ourselves. Now we can offer these services to other people, other artists we work with, other bands that we work with.” It just grew that way.

Did you ever have any overlap with the baseball stuff and the music?

For a long time, both brands existed completely outside of each other. I really didn't acknowledge Sully's in the Bridge Nine world and vice versa. As we started to realize there is a lot of crossover, some of our artists were wearing our t-shirts when they would tour for Sully's. When you're a Boston band, you want to rep Boston. That's the basis of our business.

I started to use Sully’s as a way to try out products that I would later use for Bridge Nine. I think it was 2005 or 2006, when I started making flags, because what better way to be loud and promote a slogan? We were doing so well with T-shirts. I said, “Let's put these on banners, something that people can put up in their dorm room. They can hang from their window. They can maybe bring to a game before it gets taken away because it's too big.”

I started putting some of the Sully’s slogans on flags and did very well with that. As a teenage punk rock fan, I wished that I could have had a banner for some of my favorite bands. They didn't really exist. Tapestries were something that if you were a fan of Led Zeppelin or Metallica or some of these much bigger stadium bands, you could find that for your wall, but it didn't exist for punk rock bands. I started making flags for Bridge Nine artists. They were incredibly popular.

In fact, I even started a short-lived fourth business called Punk Flags where I was just brokering flags for other artists that wanted to have this product on tour. I would start making things for both brands. I would just label them differently. I'd make sports flags for Sully’s. I'd make band flags for Bridge Nine. That translated to other products like enamel pins, patches, obviously, all sorts of apparel.

When you go back to Fenway, to Boston, how do you feel? Do you take your daughter and say, “Hey, this is where I used to work”?

It's funny because for years, I was such a fixture at Fenway Park. We were at every game, I think for almost 17 years, I think from 2000 to 2017. We would have vendors outside of the stadium. I remember when I stopped doing that, it actually was bittersweet, because I'd be like, “Man, we used to make so much money being down here. I can't enjoy myself.”

It took a little while for me to be able to have that separation where it didn't matter. I didn't have to be hustling. I didn't have to be trying to work an angle for something. I can just enjoy it. I've been able to bring my daughter to games, and that's been a lot of fun. I bring her with some of her friends. My dad took me to Fenway when I was 10. Having the opportunity to bring my daughter has been very, very cool.

The area's changed. It's obviously, I don't want to sound like a boomer, it's all condos now. Seeing how the area has changed has been an interesting evolution. Our first real office was in a basement across the street from Fenway Park, right diagonal from what was Yawkey Way and is now Jersey Street. That building was torn down in the mid-2000s and is now a 14-story, beautiful, mixed-use building with a pool on top. It is weird going down there and seeing how much it's changed. Ultimately, I think it serves that area just fine, so I don't have any complaints.

Teenage you wouldn't be able to afford the office space there anymore.

No. I mean, there are people that still sell t-shirts around the stadium, and there are people that have had opportunities that have eclipsed, I think, what we did at that time. What we were doing, it really wouldn't fit into 2026.

Fenway Punk is out today and available for purchase where books are sold.

Building a Record Label from a Street Merch Empire